ITS back! New for 2017, with a new venue and different time of year, but still loads of fun and subtle elements of physics, chemistry, food science and engineering, the Tallest Jelly Competition will rise again this year

DOWNLOAD THE FLYER HERE FOR MORE DETAIL

The challenge is out there, which school can make the Tallest Jelly? In association with this year’s Royal Norfolk Show, TSN supported by the RSC and IOP is re-launching the Tallest Jelly competition: promoting scientific enquiry, creativity and ingenuity combined with elements of Food technology, chemistry and engineering and of course that essential scientific ingredient, fun!

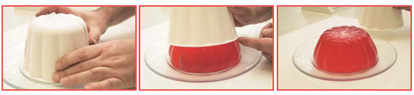

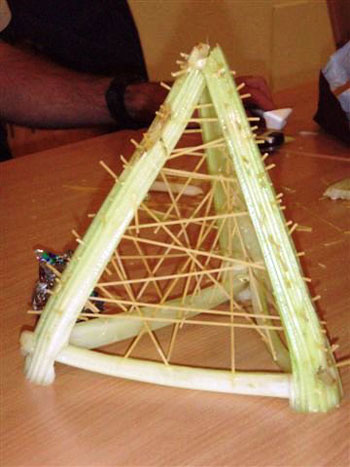

It is REALLY difficult to make a jelly more than 10cm tall due to the weak gel strength. Try it and see for yourself. To make it taller you either need to increase the gel strength (in this competition that's cheating) or give the jelly structure using edible materials such as fruit, sponges or pasta. Let your imagination run wild!

Entries are open to any primary age group and prizes will be awarded for all entries that successfully bring their jellies to the Final at the Royal Norfolk Show on Thursday 29th June 2017.

...notice how the jelly collapses after the mould is removed.

We kindly acknowledge the support of the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), Institute of Physics (IOP) and the Royal Norfolk Show.

We are grateful to scientists at the former Institute of Food Research (now transitioned into the Quadram Institute) for allowing us to adopt the Tallest Jelly Competition, first conceived in 2007, and for sharing their materials (including Jelly Facts, below)

You are never too old to enjoy jelly. Half the fun lies in the spectacle: a gently wobbling pudding makes any table more exciting. Do as the Victorians did and put jellies down the centre of the table to enjoy the sight of them wobbling away throughout the meal

Jelly was first eaten by the Egyptians

The gelling agent used in most jellies is gelatin, and is sourced from animals. Before leaf gelatine was invented shaved hart’s (young deer’s) horns and the swim bladders of fish called sturgeon were used to make jelly.

Jelly used to be a food that only the rich could afford. It was hard work to make, exotic fruit was expensive and there were no refrigerators.

The Victorians were experts at making complicated jelly moulds. A shape for the jelly was of a British lion sitting on a plinth.

In the past savoury jellies were just as popular as sweet jellies. We believe Bompas & Parr have even made zebra and crocodile jelly.

Some fruits like pineapple won’t set as jellies as they contain enzymes that break down the protein bonds. Others like blackberry and strawberry make wonderful jellies.

Gelatin the main gelling agent for jelly was used as a blood plasma substitute during World War II.

In 1997 the Army’s Logistics Corp helped to make the world’s biggest jelly at Blackpool Zoo. The jelly was almost one metre tall by seven metres wide and took about 12 hours to set with a blast chiller.

If you eat too much jelly it can be a mild laxative!

On March 17, 1993, technicians at St. Jerome hospital in Batavia tested a bowl of lime jelly with an EEG machine and confirmed the earlier testing by Dr. Adrian Upton that a bowl of wobbling jelly has brain waves identical to those of adult men and women.

Jelly doesn’t wobble underwater

What is jelly made of?

Why does jelly set?

The key to jelly setting is down to the protein collagen!

About 25% of the protein in your body is collagen which is made of three protein fibres twisted round each other – triple helix.

Collagen in animal skin and bones is broken down by heat and treatment with acids and alkalis. Bonds between collagen molecules (intermolecular bonds), bonds in the molecules (intramolecular bonds) and hydrogen bonds are all broken down, making gelatin.

When protein loses its shape it denatures.

When the gelatin is heated and mixed with water the protein fibres come apart and unravel. As it cools they coil up again and intertwine trapping the water molecules between them. This mixture of water molecules spread evenly in a collagen matrix is known as a hydrocolloid.

The concentration of gelatin needs to be about 1% to form jelly

The strength of a gelatin-based gel is its bloom strength and can be measured with a penetrometer or gelometer.

Jelly has a melting

temperature below 35°C.

Our body has a temperature around 37°C.

This means jelly has that perfect melt in the mouth sensation releasing the flavour trapped in the jelly.