Allan Pacey is Senior Lecturer in Andrology at the University of Sheffield and is also Head of Andrology for Sheffield Teaching Hospitals. He has research interests in male reproductive health and human sperm function. He fronted the highly successful ‘Great Sperm Race’ shown on C4 in 2009 and more recently was science adviser on the feature film Donor Unknown.

Stephen Franks, Professor of Reproductive Endocrinology at Imperial College, London and Consultant Endocrinologist at St Mary’s and Hammersmith Hospitals, London. He has both clinic and laboratory based programmes of research in reproductive hormones and a major interest in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

Dagan Wells has been involved in preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and the study of human gametes and embryos for almost two decades. He was responsible for developing the first method for reliably screening the entire chromosome complement in embryos and oocytes. His research group has developed the technique of comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) applied to blastocyst embryos that is associated with some of the highest IVF pregnancy rates ever recorded. Dagan is based at the Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Oxford.

Chris Willmott is senior lecturer in biochemistry at the University of Leicester and a National Teaching Fellow. He teaches bioethics to undergraduate biomedical students and he also runs the blog Bioethics Bytes: http://bioethicsbytes.wordpress.com. Chris is also a member of the Nuffield Council for Bioethics 'Reaching out to Young People' Advisory Group.

| “brilliant mix of topics that led well from each other” |

Allan Pacey made a lively start to this popular Master Class (attended by 35 teachers), addressing issues of male fertility and infertility. Allan’s presentation highlighted key factors in sperm production and discussed in detail the many factors that can adversely affect fertility. It then came as little surprise when Allan revealed that sub-fertility can affect 1 in 6 couples and in approximately 50% of couples there are male infertility factors involved. Semen production and quality are clearly vulnerable to a range of factors but it was particularly interesting to note that the criteria for defining ‘normal’ has changed over the years both in terms of the characters used in the definition and their ‘acceptable limits’ whether it was sperm number / motility / morphology or concentration. Yet semen analysis has remained the main diagnostic tool over the years.

Allan Pacey made a lively start to this popular Master Class (attended by 35 teachers), addressing issues of male fertility and infertility. Allan’s presentation highlighted key factors in sperm production and discussed in detail the many factors that can adversely affect fertility. It then came as little surprise when Allan revealed that sub-fertility can affect 1 in 6 couples and in approximately 50% of couples there are male infertility factors involved. Semen production and quality are clearly vulnerable to a range of factors but it was particularly interesting to note that the criteria for defining ‘normal’ has changed over the years both in terms of the characters used in the definition and their ‘acceptable limits’ whether it was sperm number / motility / morphology or concentration. Yet semen analysis has remained the main diagnostic tool over the years.

Allan was followed by Prof. Steve Franks whose talk addressed some of the challenges faced in unravelling female fertility. Steve began by describing in the detail the complexities and interactions that make-up what he described as “the miracle of the ovulation cycle.” Females in contrast to males are born with their lifetime’s supply of oocytes, which represents in excess of 1 million eggs of which in a lifetime approximately 400 are ovulated, the remainder dying along the way (a process known as atresia). The number of oocytes declines slowly up to mid thirties, then rapidly between 35 and 40, their depletion marking the onset of the menopause. With several follicles developing during each menstrual cycle, the role of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) is critical to ensure single egg ovulation, its level dropping significantly 5 to 15 days into a cycle.

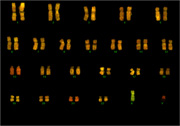

With 5 hormones involved in the complex regulation of ovulation, infrequent, irregular or a lack of ovulation is common and such endocrine causes of infertility very common (c. 30%), again in contrast to males. Blocked fallopian tubes accounting for the other primary source of female infertility. In many cases hormone treatments can restore fertility sometimes via portable pulsatile infusion pumps developed in the last 20 years and Steve highlighted some case studies. The final part of his talk explored our knowledge of the menopause and specifically premature menopause showing how techniques such as confocal microscopy and immuno-fluorescence were allowing scientists to visualise communication between eggs and their supporting (granulosa) cells. It was hoped that this work would increase our understanding of how cells start growing and changing so that we can learn more about the signals that control follicle growth.Our first two speakers had highlighted some of the barriers to conception and after coffee, Dagan Wells went on to describe new techniques in Assisted Conception most commonly In-Vitro fertilisation (IVF) which now accounts for 1-5% of births in Western Europe. The techniques are well established (some 30 years after the birth of the first IVF child, Louise Brown in 1978) but researchers are looking for ways to improve the technique. IVF shows significant decreases in success rate with increasing maternal age (particularly in mothers >33 years old). This effect is not seen if using donated eggs. One of the reasons for this is an increase in frequency of chromosomal abnormalities with age, that also adversely affects implantation rates. Aneuploidy (1 or more chromosomes above/below the normal number) is common in humans and those over 40 years old can have up to 50% aneuploidy (human chromosomes 15 and 22 being the most susceptible).

With standard embryo evaluations not revealing those embryos with the wrong number of chromosomes how can researchers tackle these challenges? Dagan discussed the use of pre-implantation genetic screening techniques using FISH (fluorescent in-situ hybridisation) of chromosomes from fertilised embryos. The anticipated benefits of these methods for IVF patients - a reduction in aneuploid syndromes, reduced miscarriage rate and increased implantation/pregnancy rates – are yet to be seen in randomised trials. Having discussed possible reasons for this, including incomplete chromosome coverage and crude biopsy methodologies Dagan highlighted further developments to overcome these difficulties.

With standard embryo evaluations not revealing those embryos with the wrong number of chromosomes how can researchers tackle these challenges? Dagan discussed the use of pre-implantation genetic screening techniques using FISH (fluorescent in-situ hybridisation) of chromosomes from fertilised embryos. The anticipated benefits of these methods for IVF patients - a reduction in aneuploid syndromes, reduced miscarriage rate and increased implantation/pregnancy rates – are yet to be seen in randomised trials. Having discussed possible reasons for this, including incomplete chromosome coverage and crude biopsy methodologies Dagan highlighted further developments to overcome these difficulties.

Micro-array comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) allows the copy number of all chromosomes to be determined and screened and the use of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) to spot mutations in DNA sequences that are associated with single gene disorders. Both techniques require small amounts of DNA to be taken from growing embryos (with little or no effect on embryo biopsy).

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) techniques were developed as an alternative to prenatal diagnosis, for couples at risk of transmitting an inherited disease to their offspring. They involves checking the genes of embryos created through IVF for particular genetic conditions. PGD screens for single gene mutations are now common and the HFEA allow screens for over 100 conditions (more here). Theoretically it is possible for any disease provided the causative mutation is known. A very readable ‘lay-mans’ description of PGD can be found at this link written by colleagues at UCL, http://www.ucl.ac.uk/PGD/further-information/)

Our final speaker summarised the many ethical and social questions posed by the techniques that our first 3 speakers had highlighted. Dr. Chris Willmott began by discussing issues of childlessness and the definition of being a parent – for example, genetic mother / gestational mother / care-giving mother. He then looked at the consequences of agelessness around fertility and specific issues associated with gamete donation and identity, fertility tourism, multiple births and financial considerations for individuals and society. He concluded by looking at positive and negative aspects of PGD and whether we were getting closer to an era of ‘designer babies’ and the ability to choose the sex of our children.

| “very helpful. Has given me the confidence to have a go at the practicals with my students” |

The teachers moved to the new science training Suite at the John Innes Centre for the afternoon’s practical session. Earlier in the day, the teachers had provided eyebrow samples for a crude DNA extraction followed by PCR using the PV92 primers. These screened for the presence of the human PV92 locus in cheek cell DNA samples from the teachers. The afternoon session went through the detail of setting-up a PCR reaction and the teachers separated the products using gel electrophoresis. The techniques used by the teachers in this practical could mimick PGD (discussed earlier) in a classroom setting.

Returning to the social consequences of artificial gametes, we viewed the film, In-Vitro and looked at the resources available as support material to this short online film.

Thanks to all our speakers for providing their presentations for use in schools. Just click on the "titles below" to open the presentation: note some of these are still large files and may have be been compressed affecting their resolution if printing

Dr. Allan Pacey, University of Sheffiled, "Male-Fertility-and-Infertility" - B&W Presentation converted to pdf, file size 8 MB

Prof. Steve Franks, Imperial College - London, "Hormones-and-Fertility" - Presentation converted to pdf file, file size 17 MB

Dr. Dagan Wells, University of Oxford, "infertility treatments, genes and chromosomes" - Presentation with compressed images and converted to pdf file, file size 1.9 MB

Dr. Chris Willmott, University Leicester, Slides available via the Slideshare website, follow the link "http://www.slideshare.net/cjrw2/ethicsoffertilitytreatments